I work in the cloud security posture management (CSPM) mines. I dig for AWS misconfigurations that please the overlords, and make marketing happy when the “issues detected” number goes up and to the right. Woe is me, except I love it. Stockholm syndrome?

The worst misconfiguration check isn’t one that misses something. It’s one that generates a BS finding. Tell a customer their S3 bucket is public when it isn’t, and you’ve wasted their time. Do it twice, and they stop trusting your findings. Do it enough, and they stop logging in and ignore everything you say. The overlords start losing revenue to churn and start sending emails. Nobody likes email.

Most of today’s cloud security tools attempt to generalize checks somehow. Plerion uses Open Policy Agent (OPA) to evaluate resources against Rego policies. Write a policy once, run it against every resource, flag what doesn’t comply. Avoid spaghetti code everywhere.

That’s cool for the devs but it doesn’t always align with the real world. IAM is a beast. Resource policies, identity policies, permission boundaries, SCPs, session policies, conditions, implicit denies, explicit denies. I can stare at a policy all day and still miss the edge case that makes the difference between “publicly accessible” and “actually fine.” Yet most cloud security tools are happy to just tell you that you have a security issue based on a single layer policy check, and then expect you to squirrel-on-meth the rest of the way.

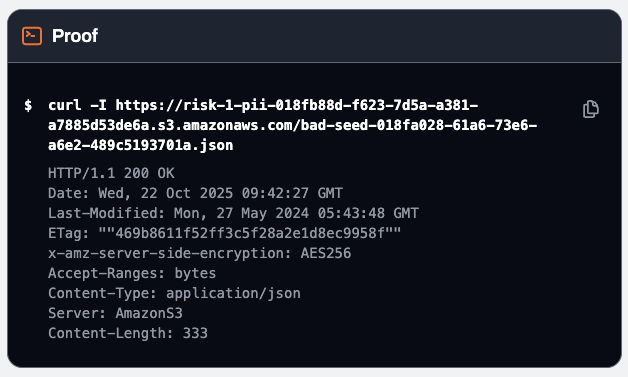

We don’t want our customers to hate us so we built something we call Fact Checker. When we flag an adverse condition finding, we don’t just trust our policy math. We empirically verify it. We actually test whether it’s true. So if we say a resource is publicly exposed, you can see the execution log of the fact checker trying to access the resource from the command line on the internet. You can also take that same command, copy and paste, and run it yourself to verify as you investigate and fix.

This post isn’t about the product though. It’s about the methodology we figured out along the way, which applies whether you’re building a CSPM, doing bug bounty, or just trying to validate your own IAM policies without accidentally torching prod.

Security researchers face the same challenge. They want to find potentially exposed resources and need to prove it without losing their bounty because they broke the rules. They can’t just go breaking stuff and expect companies to pay for the privilege.

So how do we, and how can you, test AWS resource access without angering the people that pay the bills? Keep reading…

What Makes a Test “Safe”

Before we can test safely, we need to define ‘safe’. Here’s the mental model I use:

Imagine the cloud infrastructure you’re testing belongs to a hospital where I’m a patient. They have patient records, appointment schedules, prescription data. Now imagine the person running the test is someone who’d love to cause harm to me and others. What should they be able to do? This is how companies often see all outsiders until proven or contracted otherwise.

My answer is they can learn whether cloud resources exist, how much access is available, maybe some basics about resources like sizes. Nothing else. They can’t read patient data. They can’t infer what patients and diseases are being treated. They can’t disrupt operations. They can’t leave a mess behind.

Don’t Read Sensitive Data

…unless you’re a contracted party with explicit permission to do so. “Don’t read user-generated content” sounds simple, but there’s a spectrum here.

Nope:

- Message contents (SQS messages, SNS notifications, chat logs)

- File contents (S3 objects, EFS files)

- Database records

- Secrets and credentials

- Anything a customer explicitly stored

Probably fine:

- Resource ARNs (you already have these to test)

- Service-generated metadata (creation timestamps, version numbers, regions)

Probably fine but requires judgement:

- Policy documents (these describe access, they’re not customer data)

- Encryption configuration (KMS key IDs, algorithm choices)

Requires even more judgment:

- Resource names and tags. These range from innocuous (

my-test-queue-1) to genuinely sensitive (prod-patient-notificationstells you they’re handling patient data,CostCenter: Oncologytells you which department). Just because it’s “only a name” doesn’t mean it’s safe to expose. You’re not reading the messages, but you might be revealing what kind of messages exist. - Queue depth and message counts. Knowing there are 50,000 messages in a queue reveals activity patterns. Is that sensitive? Depends on context.

- Error rates and delivery status. Same deal. Operational metadata that could reveal usage patterns.

The principle: could this information help an attacker understand what the customer is doing with this resource, beyond the fact that it exists? If yes, think twice.

Don’t Change State

This one seems obvious but has nuance too.

Clearly bad:

- Deleting resources

- Purging queues

- Modifying policies or configurations

- Adding data, modifying data, removing data

- Adding permissions that didn’t exist before

- Sending messages that get processed

Actually fine:

- Operations that succeed but change nothing (we’ll get to these)

- Reading metadata (reads don’t mutate)

- Requests that fail validation (nothing executes)

- Removing a tag that isn’t there (succeeds, removes nothing)

The gray area:

- Adding a permission that already exists (idempotent, difficult in practice)

- Setting an attribute to its current value (no-op)

The test: if you ran it a thousand times, would the resource behave identically to when you started? If yes, you’re probably fine.

Fast and Repeatable

Good test engineering matters for these reasons:

Scale. A CSPM platform runs millions of checks a day across thousands of customer accounts. A bug bounty researcher scanning for exposed resources might hit hundreds of thousands of endpoints. If each test takes 30 seconds, you’re not testing at scale. You’re not testing at all. The test needs to complete in milliseconds, not seconds.

Cost. Every API call has a cost, whether that’s direct (AWS charges), indirect (compute time), or operational (log volume, alert noise). A test that makes 10 API calls per resource might be fine for one-off investigations. For automated verification at scale, that’s 10 million extra API calls. The system becomes too expensive to run. Each test should be as cheap as possible: ideally one request, one response, done.

Rate limits. AWS throttles API calls. Hit the limits and your test system starts failing. That’s annoying but recoverable. What’s worse is if you’re running tests inside a customer’s account using an assumed role. Now you’re consuming their API quota. Aggressive testing could throttle their production workloads. Congratulations, your safety check just caused an outage.

Determinism. A test that returns different results on different runs is useless. Worse, it’s actively confusing. If yesterday the check said “publicly accessible” and today it says “not accessible” and nothing changed, users lose trust. They start ignoring findings. The whole point of empirical verification is to provide certainty. A flaky test provides the opposite.

Reproducibility. When an engineer gets a finding, they want to verify it themselves. They want to run the same test, see the same result, gain confidence that the issue is real. Then they want to fix it and run the test again to confirm the fix worked. If the test involves spinning up infrastructure, waiting for async operations, or depends on timing, that feedback loop breaks. The engineer can’t iterate. They’re flying blind.

A good test returns in milliseconds, gives the same answer every time, and can be copy-pasted into a terminal for manual verification.

Minimize Footprint

Not a hard requirement for a CSPM but might be valuable to a red teamer. Every API call shows up in CloudTrail. Every request contributes to rate limits. If your test generates a thousand log entries per resource, that’s noise the customer has to filter through.

So the goal is: prove access exists without reading sensitive data, changing state, or breaking things. And do it quickly enough to run at scale.

So how do you verify you can read something without reading it? How do you prove you can publish without publishing? If you spend enough time in the CSPM mines, you might figure out some ways.

Technique 1: Unsigned vs Signed Requests

The hypothesis: maybe requests behave differently depending on whether they’re signed with credentials or not. Maybe we can learn something about access by comparing responses.

For SQS, this turned out to be useful. Public queues accepted completely unauthenticated requests. No SigV4 signing, no credentials, just raw HTTP. Sid scanned 1.75 billion queue URLs without any AWS credentials, and the response codes told him everything he wanted to know - which queues existed, which were publicly readable, which allowed anonymous writes.

That’s not a “safe” test in the sense we defined earlier. It’s actually accessing the resource. But if the resource is truly public, there’s no credential boundary to respect. The test reveals what anonymous internet users could do.

SNS doesn’t work this way. Unsigned requests to SNS consistently return 403, regardless of the topic’s actual policy. Even a topic with "Principal": "*" rejects unsigned requests. SNS requires SigV4 signing for everything.

Here’s what an unsigned request looks like:

POST / HTTP/1.1

Host: sns.us-east-1.amazonaws.com

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

Action=GetTopicAttributes&TopicArn=arn:aws:sns:us-east-1:123456789012:my-topic&Version=2010-03-31

Response:

HTTP/1.1 403 Forbidden

<ErrorResponse>

<Error>

<Code>MissingAuthenticationToken</Code>

<Message>Request is missing Authentication Token</Message>

</Error>

</ErrorResponse>

For SNS, the unsigned request always fails with MissingAuthenticationToken. The signed/unsigned comparison tells us nothing useful here. The technique that worked brilliantly for SQS doesn’t apply. Services behave differently. Always test your assumptions.

Technique 2: Metadata Reads

Some read operations return information about a resource without returning user data.

GetTopicAttributes returns the topic policy, owner account, and delivery settings. It doesn’t return the messages. You learn whether the topic is misconfigured without reading what customers sent to it.

Here’s what a successful metadata read looks like:

POST / HTTP/1.1

Host: sns.us-east-1.amazonaws.com

Authorization: AWS4-HMAC-SHA256 Credential=.../sns/aws4_request, ...

Action=GetTopicAttributes&TopicArn=arn:aws:sns:us-east-1:123456789012:my-topic&Version=2010-03-31HTTP/1.1 200 OK

<GetTopicAttributesResponse>

<GetTopicAttributesResult>

<Attributes>

<entry><key>Policy</key><value>{"Version":"2012-10-17",...}</value></entry>

<entry><key>Owner</key><value>123456789012</value></entry>

<entry><key>SubscriptionsConfirmed</key><value>3</value></entry>

<entry><key>SubscriptionsPending</key><value>2</value></entry>

<entry><key>DisplayName</key><value>my-notifications</value></entry>

</Attributes>

</GetTopicAttributesResult>

</GetTopicAttributesResponse>

No message contents but the display name is user generated content and could in theory contain something sensitive so it’s not cut and dry.

Similarly:

- SQS

GetQueueAttributestells you queue depth and settings, not message contents. - Secrets Manager

DescribeSecretreturns rotation config without the secret value. - S3

HeadObjectreturns metadata without downloading the object body.

Metadata is usually fair game. User-generated content is not. The API tells you what kind of data you’re getting.

Technique 3: No-op Operations

Some write operations can succeed without changing anything.

In the SQS post, this meant “API requests without any parameters.” Same idea applies to other services.

Empty inputs. Pass an empty array where an array is expected. Call a batch operation with zero items. The operation succeeds, proving you have permission, but nothing actually happens.

Non-existent targets. UntagResource with a tag key that doesn’t exist? It succeeds in removing nothing. RemovePermission with a label that was never there? Same deal. You can’t delete what doesn’t exist.

Idempotent values. SetTopicAttributes setting SignatureVersion=1 when that’s already the default and rarely changed will almost certainly result in no change but there is still some risk, assuming you can guarantee the default. AddPermission granting the owner account a permission they already have by virtue of ownership could also be harmless.

Here’s the UntagResource request and response with a nonexistent tag key:

POST / HTTP/1.1

Host: sns.us-east-1.amazonaws.com

Authorization: AWS4-HMAC-SHA256 Credential=.../sns/aws4_request, ...

Action=UntagResource&ResourceArn=arn:aws:sns:us-east-1:123456789012:my-topic

&TagKeys.member.1=nonexistent-key-12345&Version=2010-03-31HTTP/1.1 200 OK

<UntagResourceResponse>

<UntagResourceResult/>

</UntagResourceResponse>

The 200 proves you have sns:UntagResource permission. But the tag key never existed, so nothing was removed. The resource is identical to before.

If the operation returns 200, you proved you have permission. If it returns 403, you don’t. Either way, nothing changed.

Technique 4: Malformed Request Probes

Here’s where it got interesting to me.

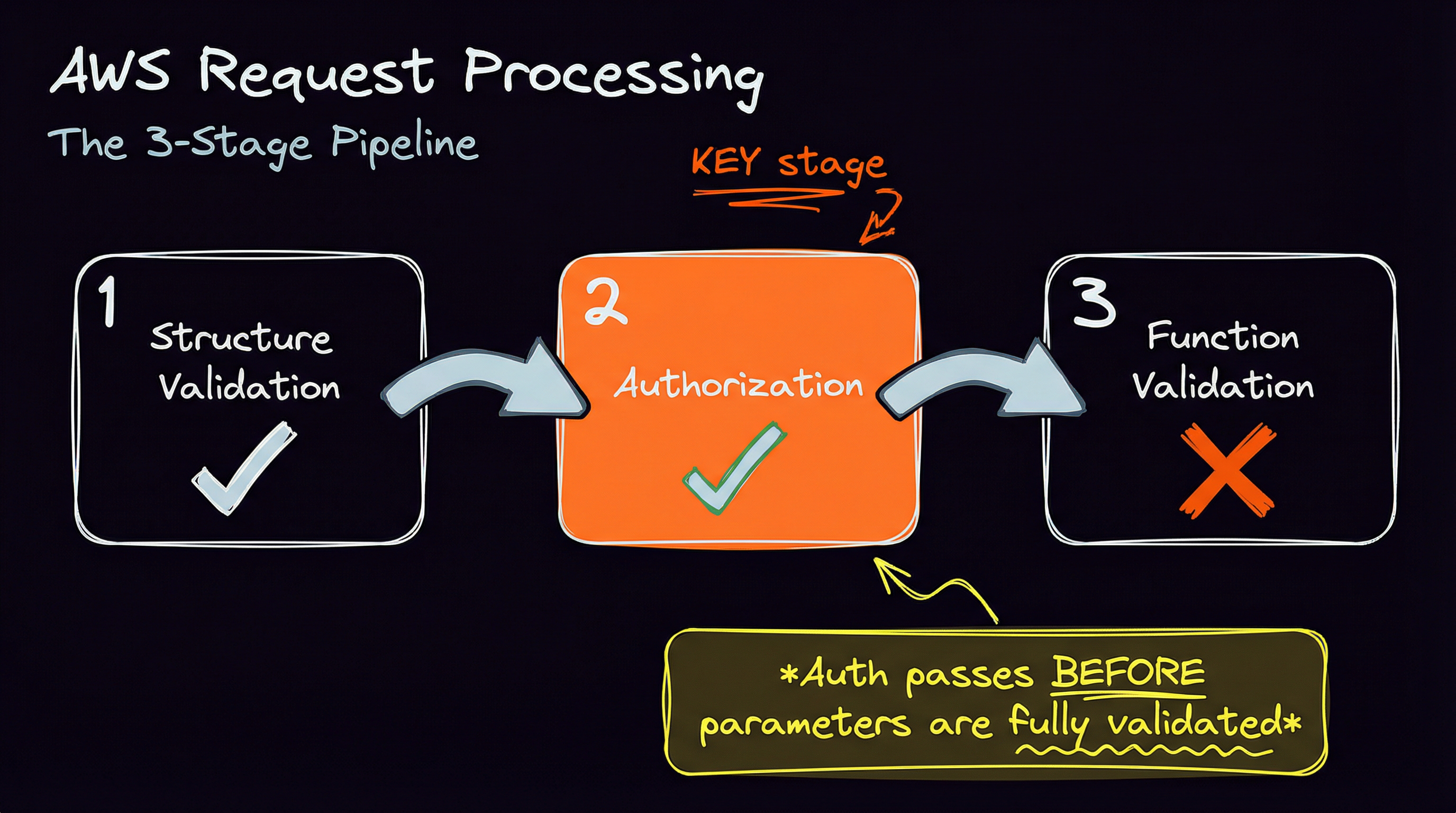

AWS processes requests in sequential stages, at least according to my best intuition:

- Structure validation: Is this even a valid request format?

- Authorization: Are you allowed to do this?

- Function-specific validation: Are your parameters correct for this operation?

The important thing is that authorization happens before full parameter and business logic validation by the target function.

This means you can craft requests that pass structure validation, pass authorization, and then fail on function-specific validation. AWS tells you “yes, you’re authorized” and then “but your request is malformed.”

That’s a safe probe. You proved permission without executing the action.

Example mutations:

Publishwith an empty message body → InvalidParameter if authorized, AccessDenied if notSubscribewith an invalid protocol → InvalidParameter if authorized, AccessDenied if notAddPermissionwith a bogus action name → InvalidParameter if authorized, AccessDenied if not

Here’s Publish with an empty message against a topic you have access to:

POST / HTTP/1.1

Host: sns.us-east-1.amazonaws.com

Authorization: AWS4-HMAC-SHA256 Credential=.../sns/aws4_request, ...

Action=Publish&TopicArn=arn:aws:sns:us-east-1:123456789012:allowed-topic&Message=&Version=2010-03-31HTTP/1.1 400 Bad Request

<ErrorResponse>

<Error>

<Code>InvalidParameter</Code>

<Message>Invalid parameter: Empty message</Message>

</Error>

</ErrorResponse>

The same request against a topic you don’t have access to:

HTTP/1.1 403 Forbidden

<ErrorResponse>

<Error>

<Code>AuthorizationError</Code>

<Message>User: arn:aws:sts::123456789012:assumed-role/MyRole/user is not authorized

to perform: SNS:Publish on resource: arn:aws:sns:us-east-1:123456789012:denied-topic</Message>

</Error>

</ErrorResponse>

The 400 proves you’re authorized to publish. The 403 proves you’re not. Neither one actually sends a message.

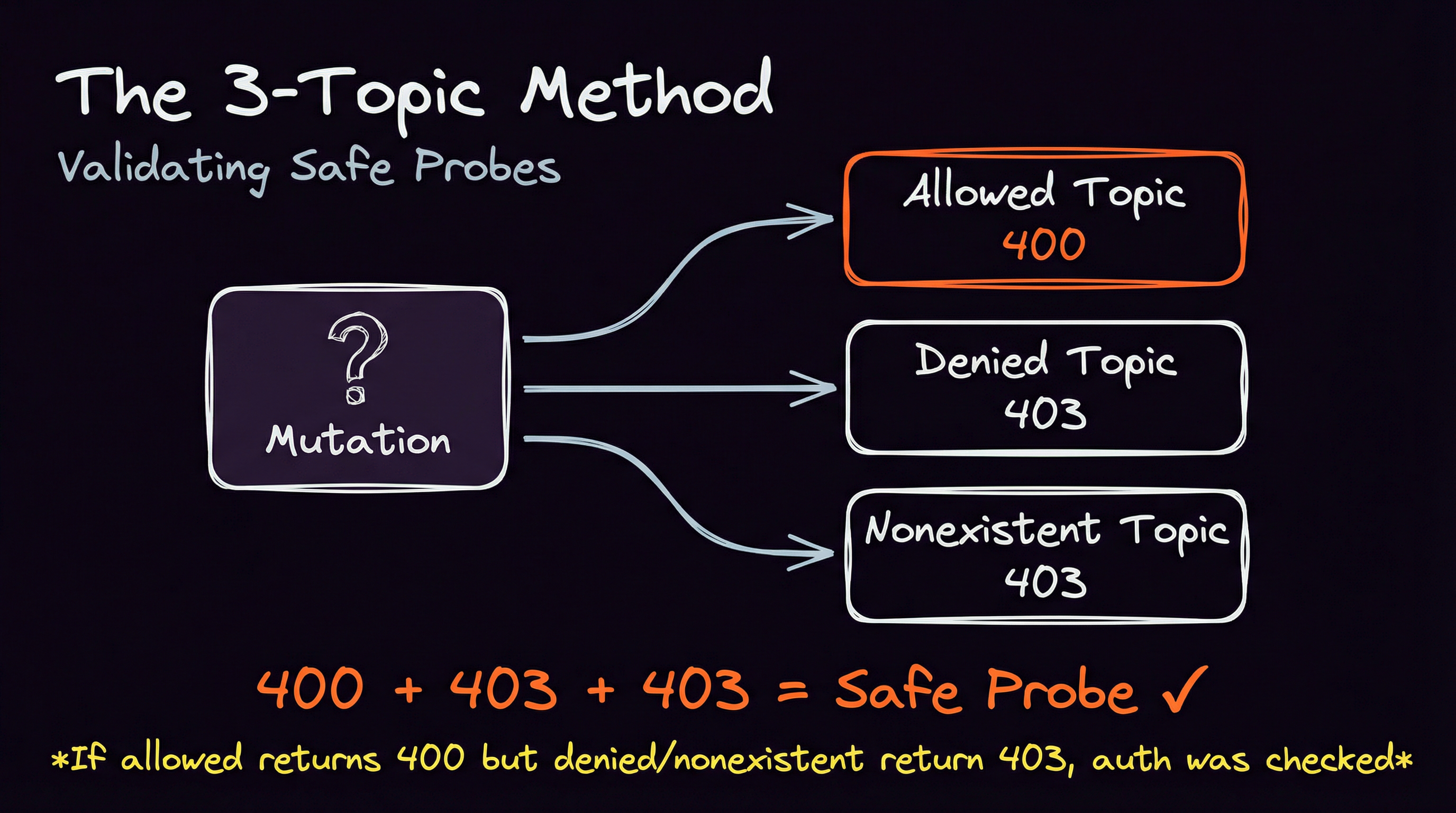

Validating Probes: The 3-Topic Method

Here’s the problem: how do you know a malformed request actually proves authorization, rather than just failing before authorization runs? Not all APIs are strict about returning 400s, especially for security reasons. Many AWS APIs will return a 403 when the request is malformed, or even if it does not exist and yet others might do the opposite.

If your mutation triggers pre-authorization validation but returns a 400, you learn nothing about permissions.

The solution is to test the same mutation against three pre-configured targets.

- Allowed resource: One you control and have given yourself full access to.

- Denied resource: One you definitely cannot access because there’s no policy that allows it or there’s an explicit deny.

- Non-existent resource: A random ARN pointing to a resource that does not exist.

Compare the responses:

| Allowed | Denied | Nonexistent | What it means |

|---------|--------|-------------|--------------------------------------------|

| 400 | 403 | 403 | Safe probe! Auth passed, validation failed |

| 200 | 403 | 403 | Action succeeded (use no-op techniques) |

| 400 | 400 | 400 | Pre-auth validation. Useless. |

If Denied and Nonexistent both return 403 but allowed returns 400, you’ve confirmed auth was checked before the validation error. That mutation is a safe probe.

Conversely, if Allowed and Denied both return the same response or Allowed and Nonexistent return the same response , the validation happened before authorization.

sns-buster: Automating Safe Probes for SNS

We built sns-buster to automate all of these techniques for SNS topics. It’s open source and you can use it as long as you include the original copyright notice in an obvious place.

What it does:

- Tests 14 SNS API actions (reads and writes)

- Runs unsigned and signed requests

- Applies 30+ parameter mutations per action

- Uses the 3-topic method to identify safe probes

- Outputs evidence without touching customer data

sns-buster --arn arn:aws:sns:us-east-1:123456789012:target-topic --safeUseful mutations found:

Publish + empty-message:

allowed=400 denied=403 nonexistent=403

Safe probe: auth passed then "InvalidParameter"

UntagResource + nonexistent-tag-key:

allowed=200 denied=403 nonexistent=403

No-op probe: 200 success with no side effects

Every finding is backed by a logged request/response pair you can reproduce. No trust required. You can review each of the mutation permutations and copy paste them where you need them.

SNS Oddities Worth Knowing

Building sns-buster meant learning SNS’s quirks the hard way. Some of these surprised me even though I’ve been playing with SNS for over a decade.

You can’t use SNS:* in resource policies. Try adding "Action": "SNS:*" to a topic policy and AWS rejects it. You have to enumerate specific actions. I found the valid set by adding them one by one until the policy saved. Here’s a policy that actually works for exposing a topic:

{

"Version": "2012-10-17",

"Statement": [{

"Effect": "Allow",

"Principal": "*",

"Action": [

"SNS:Publish",

"SNS:Subscribe",

"SNS:GetTopicAttributes",

"SNS:ListSubscriptionsByTopic",

"SNS:ListTagsForResource",

"SNS:TagResource",

"SNS:UntagResource",

"SNS:SetTopicAttributes",

"SNS:AddPermission",

"SNS:RemovePermission",

"SNS:GetDataProtectionPolicy",

"SNS:PutDataProtectionPolicy",

"SNS:DeleteTopic"

],

"Resource": "arn:aws:sns:us-east-1:123456789012:my-topic"

}]

}

For the full list of actions that SNS supports, check the JSON formatted SNS service authorization reference.

The console makes it hard to expose topics. I love AWS’ recent commitment to secure defaults. When you create a topic through the AWS console, it adds a StringEquals condition on AWS:SourceAccount by default, restricting access to your own account. You have to actively remove these guardrails to create a truly public topic. This is good design on AWS’s part. It means most exposed topics are intentional (or the result of Infrastructure as Code that didn’t include the guardrails).

Severity depends on context. Not all exposed topics are equal because not all topics expose the same actions. GetTopicAttributes leaks the access policy, owner account ID, display name, subscription counts, KMS key ID, and delivery settings. That’s reconnaissance gold, but it’s not data access. Publish lets an attacker inject messages. DeleteTopic is destructive. And the impact of Publish depends entirely on what’s consuming those messages. Some subscriber systems might just log and ignore malformed input. Others might parse message content in ways that lead to injection attacks or even remote code execution. The topic’s exposure is just the beginning.

Subscription ownership is complicated. When you subscribe to an SNS topic, the subscription can be owned by either the topic owner or the subscriber, depending on who created it. The Unsubscribe API says that if authentication is required, only the subscription owner or topic owner can unsubscribe. But if authentication isn’t required, anyone can request an unsubscribe (though the endpoint gets a cancellation notice). Cross-account subscriptions add another layer: the account that calls Subscribe becomes the subscription owner instead of the topic owner. Therefore it’s best practice is to create subscriptions from the subscriber’s account so they maintain control. For a deeper dive into cross-account patterns, see the AWS Compute Blog post on cross-account SNS integration.

Generalizing Beyond SNS

I was working on fact checker for SNS exposure but the techniques aren’t SNS-specific. They could in theory work for any AWS service.

- Metadata reads exist separately from data reads

- No-op patterns exist (empty inputs, non-existent targets)

- General validation precedes authorization which itself precedes specific validation

- Unsigned and signed requests occasionally behave differently

The methodology is the point. sns-buster is just one implementation. You could probably give this blog post to your favorite code-writing AI and ask it to prepare something similar for another service. You might even be able to get it to write a tool that takes a service as an input parameter and does service discovery and mutation mapping from scratch.

Takeaways

False positives kill trust. Empirical verification matters.

“Safe” means no UGC access, no state changes, no destruction. Four techniques get you there: unsigned/signed comparison, metadata reads, no-ops, and malformed request probes. The 3-topic method validates that a probe actually tests authorization.

sns-buster automates this for SNS. The methodology extends further.

The best security check is one that’s right. The second best is one that verifies itself without making things worse.